Jacob Maendel does not fit neatly into any particular art movement. He is an abstractionist, but even that description feels incomplete. His art builds its own vocabulary, one rooted in philosophy, mythology, and the embodied awareness of martial arts. Yet his practice is not limited to ideas alone. Nature is his constant teacher—he studies the curve of a branch, the lift of a bird’s wing, the quiet posture of a flower. These observations do not dictate what he creates but guide the rhythm of his process. The result is work that feels alive and yet distant from imitation, abstract but resonant with life. Maendel’s art is a conversation between the visible and invisible, the grounded and the spiritual. He allows form to emerge not as representation but as energy given shape, standing outside of schools, movements, or categories.

Work in Focus: 37 22 15

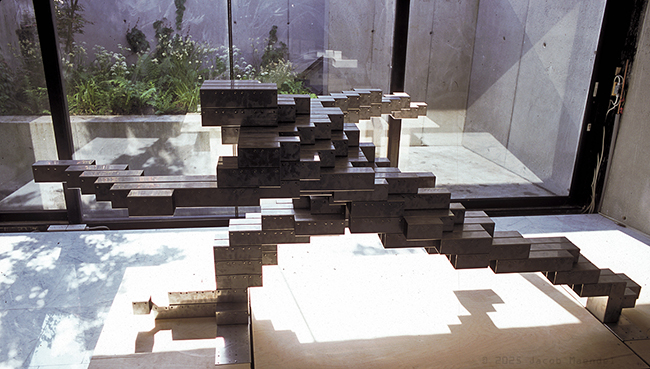

One of Maendel’s most significant works is 37 22 15 (2003), a stainless-steel sculpture measuring 111 x 66 x 45 inches. Now in the permanent collection of the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, the work demonstrates the clarity of Maendel’s language.

The title 37 22 15 refers to the (x, y, z) coordinates that define its placement within an imagined grid. This anchoring in spatial mathematics reflects his interest in structure, but the sculpture itself escapes cold geometry. Instead, it describes the movement of a walking human form—an abstraction not of body but of motion, energy, and weight. The form leans forward, pressing against the air around it, shaping and being shaped by space.

What gives the work its strength is the tension between interior and exterior. The hollow stainless steel surface suggests both presence and absence. It pushes outward, yet it is also defined by the space it encloses. In Maendel’s words, interior and exterior exist in “interdependent opposition.” Neither can be understood without the other. That paradox is central to his practice: the idea that sculpture is not an isolated object but part of a larger field of relationships.

Space as a Medium

In 37 22 15, the sculpture does not simply occupy space—it alters it. The steel form redirects the viewer’s sense of balance and scale, almost as though the room itself bends around the figure. This interplay creates a dynamic in which space and sculpture anchor one another. Each depends on the other for meaning.

The human form at the heart of the piece is less a body than an event. It represents walking, the most basic act of human progress, but abstracted until only the suggestion of motion remains. By doing so, Maendel frees the gesture from any particular body and turns it into something universal. The walk becomes a metaphor for persistence, continuity, and transformation.

Dialogue with Ancient Ideas

Though modern in its material and execution, 37 22 15 carries echoes of older traditions. Ancient philosophy often dealt with the unity of opposites, the interdependence of being and nothingness. Martial arts, another influence in Maendel’s practice, rely on similar principles—movement is always defined by stillness, attack balanced by defense, interior energy shaped by external force.

The sculpture embodies these dualities. Its polished steel surface reflects the environment around it, pulling the outside world into the piece. At the same time, the interior void asserts itself as equally important. Presence and emptiness, light and shadow, body and space—all coexist.

A Living Form

Encountering 37 22 15 in person, one is struck by its vitality. It does not appear frozen but caught mid-step, bridging past and future. Its posture hints at momentum, and that sense of forward thrust gives the work an immediacy. It does not simply sit still—it moves in the mind of the viewer.

The work invites reflection on the nature of being. What does it mean to walk, to move through the world, to push against the air? What is the relationship between a body and the space it occupies? By stripping away all but the essential, Maendel forces these questions into the open.

Conclusion

Jacob Maendel’s art is not about fitting into movements or following trends. It is about creating a language that reveals the underlying structures of existence. In 37 22 15, he transforms stainless steel into an exploration of balance, opposition, and the act of moving through space. The work stands as both object and event, presence and absence, body and void.

By rooting his process in nature, philosophy, and martial practice, Maendel reminds us that art is more than representation—it is engagement. 37 22 15 is a sculpture, but it is also a walk, a gesture, a dialogue with space. It asks us not only to look but to feel the tension between what is visible and what is not.