Vicky Tsalamata works from Athens, Greece, but her ideas seem to move freely across centuries and cultures. She creates with the awareness of someone who has spent a long time watching how people live, how cities rise and fall, and how history doesn’t sit still. Her work echoes the tensions and humor found in Balzac’s La Comédie Humaine, but she brings that sensibility into a contemporary space. Her commentary on daily life is sharp, sometimes sarcastic, and almost always rooted in the question of what it means to be human in a world that keeps rewriting itself. She looks at the present with one eye on the past, and she doesn’t shy away from asking where our worth fits into the bigger picture.

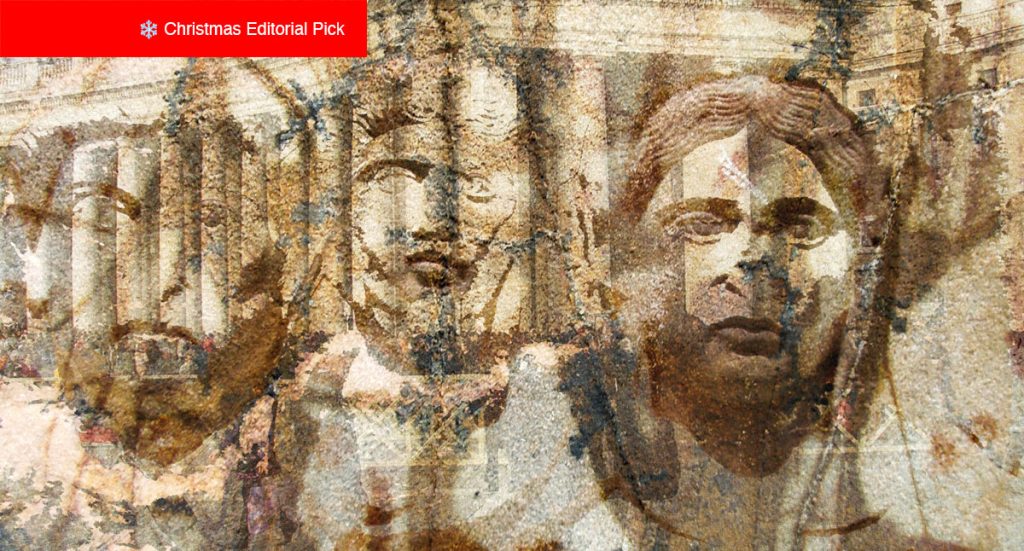

Tsalamata’s practice is grounded in mixed media, but not in the casual sense of the term. She comes from a background steeped in printmaking, research, and technical skill. Intaglio, etching, and lithography form a core part of her language. She brings these methods into conversation with photography and archival techniques, treating each medium as both a record and a reinterpretation. Her work often reads like a double exposure of time: what once was, and what now is, living in the same frame.

One of the clearest expressions of this approach appears in her series “Utopian Cities,” where she blends the physical presence of real places with the imagined layers of history and memory. This series gathers urban impressions from her travels—China, Luxembourg, Rome, Pompeii—and weaves them with etched plates, marks, and matrixes pulled from her earlier projects. It is as if she carries her own artistic history into every new city she visits. Nothing stands alone. The past leaves traces, both literal and symbolic, and she lets those traces shape the present image.

The artwork “Crossroads, maybe this garden exists in the shadow of our lowered eyelids” comes out of this ongoing project. The title itself feels like a quiet invitation. It hints at a garden that may or may not exist, a space that asks the viewer to loosen their expectations and let imagination fill in the gaps. Tsalamata describes the piece as connected to the intersection of historical context and contemporary life—the point where old ways meet new habits, and where traditions quietly pull at the sleeves of modern realities. She doesn’t push the viewer toward a fixed answer. Instead, she sets up a place of transition, a space shaped by memory, architecture, and the layered rhythm of urban life.

In Utopian Cities, this overlap between time periods becomes the core of the visual experience. The works are cultural palimpsests, layered with photography, printmaking, and remnants of older plates. Some of the etched elements come from matrixes she used years ago. She lets them resurface, almost like archaeological fragments. They don’t interrupt the new cityscapes; they fold into them. The photographic elements represent her experience wandering through different cities, absorbing how each one holds its own contradictions and desires. The printmaking elements give those impressions weight and texture, grounding them in the physical act of mark-making.

What emerges is neither a straightforward documentary nor a purely imagined world. It is something in between—a place shaped by history, technology, personal observation, and an ongoing conversation with art itself. Her cities are not perfect. They are not futuristic. They are reflections of how people move through the world now, carrying old stories in their pockets while stepping into new routines.

The project has extended beyond the visual works alone. The series eventually became the foundation for a livre d’artistetitled “The City,” created in collaboration with Gallery Lucien Schweitzer in Luxembourg. The book paired Tsalamata’s imagery with texts from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, a natural fit for her interest in how imagined and real places blur into each other. Calvino’s writing explores how cities exist both as structures and as states of mind. Tsalamata’s art does the same. She gives shape to spaces that feel familiar yet unplaceable, rooted in experience but drifting into reflection.

What makes her work resonate is its openness. Tsalamata is not trying to lecture. She observes with clarity, but she leaves room for doubt, humor, and interpretation. Her references to Balzac are not nostalgic—they’re mirrors held up to the ongoing performance of being human. The sarcasm in her work is softened by curiosity. The critique is softened by a sense of wonder. She reminds the viewer that the past is not dead, and the present is not as solid as it seems.

In a world overwhelmed by speed and noise, Tsalamata’s art slows things down. It asks you to look at what lies beneath the surface of the everyday. It traces the connections between cities, centuries, and individual lives. It gives space to the idea that we are all standing at crossroads—sometimes aware, sometimes unaware, always moving between what has shaped us and what we’re shaping next.