Sylvia Nagy works in a space where form meets technology and where the old language of ceramics is carried into a new, contemporary vocabulary. Her path has never been linear. Instead, it moves the way light travels through one of her sculptural openings—changing direction, refracted by experience, shaped by curiosity. Born and educated in Hungary, Nagy began her formal training at Moholy-Nagy University in Budapest, completing an MFA in Silicet Industrial Technology and Art. From the start, her interest sat at the crossroads of industry and imagination. Ceramics wasn’t simply craft for her; it was a field where heat, pressure, and structure became a kind of quiet engineering.

Her understanding of the material deepened when she stepped into the world of design education. Parsons School of Design invited her not just to join the academic environment but to shape it. There, she developed a course on Mold Model Making in Plaster—a technical, often overlooked foundation of ceramic work. For Nagy, plaster was not just a mold-making tool. It was a way of thinking: form built through patience, repetition, and precision. Teaching pushed her to articulate the logic behind her process, and in doing so, she strengthened her artistic language.

As her work grew, so did her travels. Artist residencies took her throughout Japan, China, Germany, the United States, and back to Hungary. Each place left its mark. Japan sharpened her eye for balance and subtle asymmetry. China widened her understanding of scale and ancient ceramic tradition. Germany challenged her sense of material efficiency. The U.S. brought her into conversations about design futures and new technologies. These influences didn’t overwrite one another; they layered themselves, forming a global map that quietly threads through her sculptures.

Her membership in the International Academy of Ceramics (IAC) in Geneva affirms her role within the field, yet Nagy does not lean on titles. What matters to her is the work: how clay responds to touch, how shape directs energy, how light interacts with space. Her pieces have found homes in museum collections in France, Spain, Korea, and beyond—not because they shout, but because they continue to reveal themselves over time.

Outside the studio, Nagy’s world expands into dance, fashion, styling, design trends, and photography. These interests might seem like separate pursuits, but for her, they feed the same intuition. Dance teaches her about movement and rhythm. Fashion helps her consider surface, color, and structure. Photography reminds her to pay attention to light and shadow. All of these threads pull into her ceramic practice in ways that feel organic rather than deliberate.

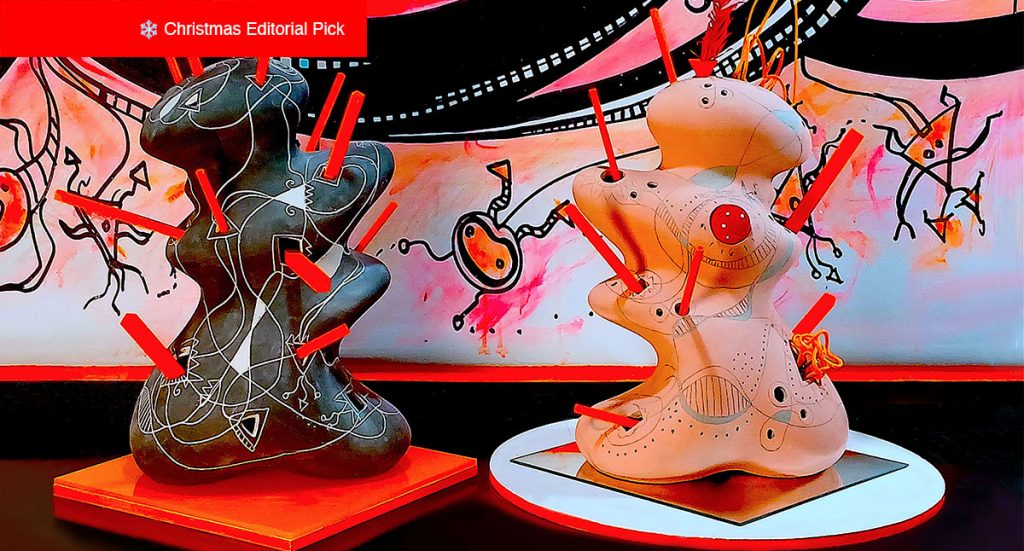

Her work Direction I.II. captures the core of this thinking. At first glance, the piece is architectural—black and orange forms shaped with clarity and intent. But the message moves deeper. Two sides of the same shape can turn in different directions, a simple statement that becomes a metaphor for choice, uncertainty, and divergence. In a world that changes quickly and often without warning, the ability to shift direction feels both necessary and disorienting. Nagy translates this feeling into sculptural language.

She cuts geometric shapes, squares, and triangular openings into the ceramic surfaces. These cuts are not decorative; they are invitations for light to travel through. When light bulbs are placed inside, the sculptures glow from within, turning them into sources of illumination. The effect is almost like watching fire held inside a structured shell—contained, yet expressive. It is a reminder that what happens inside a form matters just as much as what is seen on the surface.

Within those openings, Nagy places thin wooden sticks. Their placement feels spontaneous, yet intentional. They point in various directions, echoing the idea of unpredictability. The sticks act like small indicators, measuring and responding to change. They remind us that the world moves quickly, and the signals we follow are often scattered.

At the top of the sculptures, she adds twisted shapes, brushes, wires, and other materials that introduce another layer of meaning. These elements suggest differences in frequency—how each of us “receives” the world, how our senses tune to different signals, how perception itself is never universal. Nagy builds these ideas directly into the structure of the piece, allowing form to reflect thought.

Her approach to ceramics is practical in its construction but philosophical in its intent. She uses clay as a medium for questioning direction, energy, and human response. Her sculptures sit at the border between object and message, grounded in craftsmanship yet open to interpretation.

Sylvia Nagy’s work reflects a life lived in motion—between countries, between disciplines, between the tangible and the abstract. The pieces she creates carry this sense of movement within them. They glow, they shift, they point. They remind us that even the most solid forms are shaped by unseen forces and that light, once released, will always find its way through.