Albert Deak’s story begins in Eastern Europe, where he earned a degree in ceramics in 1989 from a prominent University of Art and Design. The training grounded him in material, form, and structure, but his path was never meant to stay inside a single discipline. Over the years, he moved from ceramics into graphics, painting, and eventually digital art, following a personal rhythm defined by curiosity rather than rules. What ties his work together is his commitment to originality. Deak prefers to build from imagination, memory, and experimentation, shaping images that question how we see time, consciousness, and the spaces we inhabit. His work doesn’t sit still. It carries the weight of experience while stretching toward ideas that feel both scientific and poetic. He approaches art as a system of exploration—one where authenticity matters more than convention.

Chronoplane Metempsis — A Visual Map of Time and Consciousness

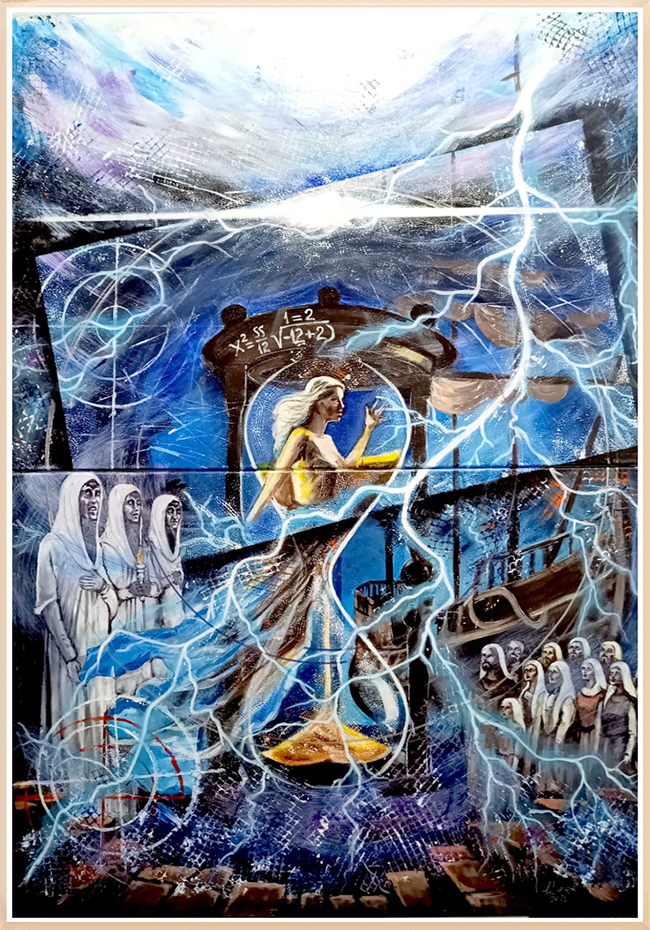

“Chronoplane Metempsis” is one of those artworks that asks you to slow down. At first glance, it looks like a bold, complex diagram—something between a cosmological chart and an abstract painting. But when you settle into it, the piece opens up into a study of how time works, how consciousness moves, and how science and philosophy can share a single canvas without crowding each other out.

The title itself gives away the project’s ambition. “Chronoplane” refers to a conceptual structure drawn from relativistic physics and the idea of multiple dimensions existing or overlapping at once. “Metempsis,” meanwhile, speaks to the shifting, cyclical movement of consciousness across different forms or states. Deak ties the two together to suggest that consciousness does not simply experience time—it travels through it, reshapes it, and is reshaped by it.

At the center of the painting, placed inside a transparent hourglass, is an ethereal human-like presence. This figure represents what Deak calls the “central consciousness.” It is not a literal portrait but an energetic form that hints at the idea of reincarnation or eternal return. The hourglass recalls the familiar symbol of time slipping away, yet the transparency suggests something more fluid: consciousness moving in cycles rather than being trapped in a countdown. The figure’s colors shift gradually from bright to dim, a choice that mirrors the Doppler Effect. Just as frequency changes relative to an observer, consciousness seems to radiate different intensities depending on its position within the flow of experience.

Surrounding this center is a dimensional structure that anchors the piece. Deak uses an inner rectangular frame to mark a different plane of existence or perception. It’s subtle but essential—the suggestion that multiple layers of reality coexist and sometimes overlap. This layering resonates with the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which states that certain properties cannot be measured precisely at the same time. Deak isn’t illustrating the principle; he’s referencing the feeling behind it—the challenge of grasping reality fully when so many forces shift at once.

A mathematical formula appears near the structure, functioning almost like a signature of the Chronoplane. It symbolizes the laws or conditions that govern spacetime. Rather than serving as literal physics, the formula acts as a bridge between scientific language and artistic intuition. It’s there to remind the viewer that time is not just felt—it is also measured, theorized, and constantly questioned.

Three quiet observers hover at the outer edge of the composition. They aren’t human. Deak imagines them as extraterrestrial figures—cosmic witnesses. Their presence is not dramatic; they don’t intervene. Instead, they seem to be watching the unfolding of time and consciousness from a distance. Their perspective introduces an interesting shift: how does the universe look when viewed from outside humanity’s timeline? What does consciousness mean when you remove human-centered limits?

At the bottom of the composition sits a medieval ship that appears misplaced, abandoned, or stranded. Deak includes it as a symbol of “obsolete time”—the old idea that time moves in a straight, predictable line from past to future. The ship represents traditions or worldviews left behind, unable to navigate the multidimensional world of the Chronoplane. It’s a gentle reminder that our understanding of time has always changed and will keep changing.

Taken together, the painting works as a layered diagram, but also as something more poetic. It reflects Deak’s impulse to merge imagination with observation. “Chronoplane Metempsis” maps the universe not as something fixed, but as something alive—where consciousness moves in cycles, dimensions overlap, and the story of time expands far beyond what we once believed.