Maria Olga Vlachou is an artist who treats cultural memory not as something to be archived, but as something to be awakened. Working out of Athens, she positions herself in a rare space between ethnography, technology, and artistic ritual. Her focus is intangible heritage—traditions carried through gestures, patterns, stories, and symbols that have survived not because they were written down, but because they were embodied across generations. Her work asks a deceptively direct question: How does one preserve something that has no physical form? How do you protect a cultural memory that exists in motion, in repetition, in sound, in the hands that craft textiles or trace symbols?

For Vlachou, the answer has been POSTFOLK, a long-term artistic research project that explores Greek folk patterning through the digital lens. She has invented a language of Digital Pointillism: thousands of dots arranged carefully, one by one, referencing embroidery motifs that appear across villages, regions, and eras. Rather than replicating traditional textiles, she transfers their structural intelligence into new visual systems. Embroidery, after all, is already a kind of code—repetition, geometry, protection, identity, and storytelling threaded into fabric. Vlachou moves that code into the digital environment, making each dot a pixel, each pixel a stitch, and each work a map connecting the past to contemporary visual culture.

Her process is not automated. That choice matters. Every dot in her compositions is intentionally placed, echoing the slow rhythm of craft. The decision not to automate speaks to something deeper: a refusal to flatten heritage into decoration or reduce culture to easily reproduced graphics. Instead, she brings ritual labor into the technological sphere. She treats digital creation with the same patience as needlework—the body moves, the eye selects, the hand repeats. The digital screen becomes a loom.

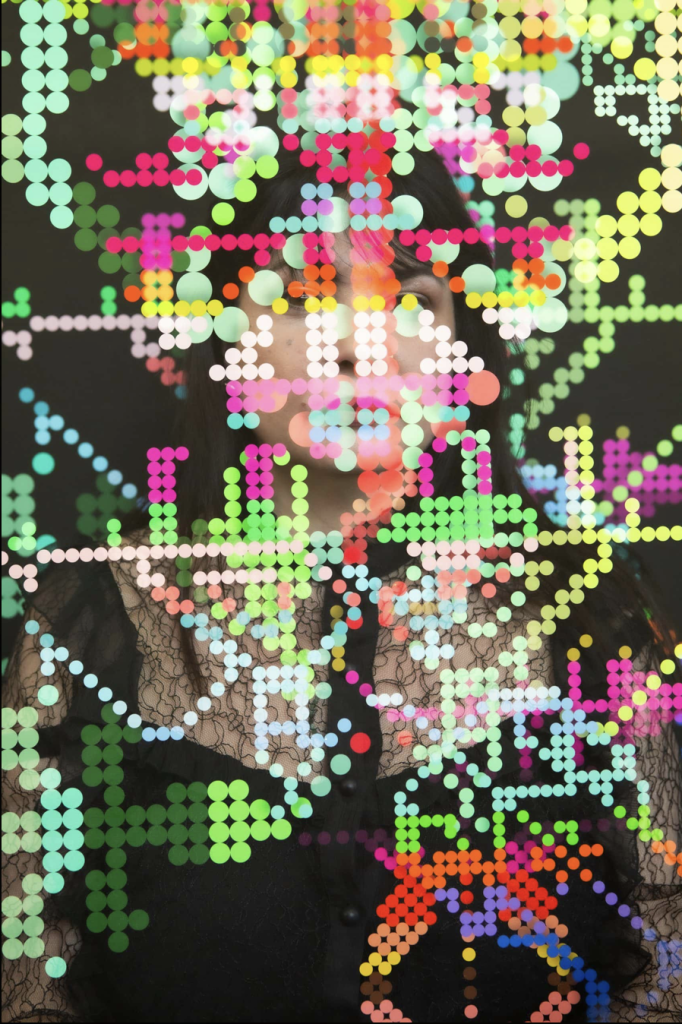

Her works emerge from this structure like woven apparitions bursting through the dark background of the digital void. In the image provided, brightly colored dots scatter across a portrait, cascading like a tapestry suspended in midair. The face behind the pattern is only partially visible, hinting at identity without revealing it. This is intentional. Heritage, Vlachou suggests, is not simply personal identity, but something collective. It is bigger than the individual, stronger than biography.

The overlay of the POSTFOLK code across a human form mirrors the reality of tradition itself: we carry cultural memory on our bodies. We inherit it without choosing it. It shapes us before we understand it. Here, the face becomes a landscape—embroidered, pixelated, layered with symbolic language. Vlachou connects the ritual past to the digital present through sensation rather than nostalgia. She is not longing for an old world. She is building a new one out of its fragments.

Her dots vary in scale and brightness. Some glow like neon circuitry, some are muted like fading threads. Viewers experience the work as both textile and data visualization, collapsing craft and technology into one surface. The palette is vivid—greens, pinks, blues, oranges—forming grids, directional lines, and abstract figures that recall weaving structures from Greece’s long folk history. It is not an appropriation; it is an active continuation.

The key to understanding Vlachou’s thinking is her claim that these works circulate heritage through “the digital ether.” In a world where museums and archives rely heavily on physical artifacts, she argues for the survival of practices that cannot be stored in glass cases. Intangible heritage includes songs, dances, prayers, blessings, embroidery codes believed to protect the body, and symbolic gestures handed down through domestic space. Much of this cultural matrix remains undocumented in official history because it was developed and maintained by anonymous women whose work was not recognized as art or literature.

Vlachou’s practice repositions those anonymous artisans at the center of contemporary visual culture. The digital space becomes a form of justice—recognition offered through aesthetics. Her work confronts the long-standing hierarchy between folk craft and fine art, questioning why cultural memory is treated as ethnography rather than artistic expression.

Her collaboration history reflects this wider conversation. Working with institutions such as the Greek National Opera and the Victoria G. Karelias Collection, she creates works designed to function as “living archives”—projects that situate her practice within broader cultural ecosystems. Rather than speaking exclusively to the art market, she engages with heritage, performance, and museum environments. Her pieces do not merely hang on walls; they operate as bridges between communities, research fields, and senses of belonging.

In a time when many artists react to digital culture with anxiety, Vlachou approaches technology with curiosity. She does not idealize traditional craft as something lost or endangered. She refuses to pretend that embroidery or folk symbolism exist outside global technological networks. Instead, she asks how cultural information moves through those networks—and how it might be strengthened by them.

This is perhaps the philosophical core of POSTFOLK: the archive is not dead. It is alive, circulating, transforming, adapting to each technological framework we build. Dots replace stitches not out of aesthetic whim, but out of necessity. If cultural memory is to survive, it must move. Vlachou treats that movement not as dilution, but as renewal.

Her works, layered and radiant, reveal the possibility of a digital future that does not erase the past. She offers a compelling model for heritage preservation—one rooted in visual pleasure, research discipline, and cultural responsibility. Through her pointillist structures, she shows that intangible heritage is not fragile; it is resilient.

Maria Olga Vlachou makes art that remembers. More importantly, she makes art that ensures others remember too.